In the wee morning hours of April 12, 1861, historians agree that the star shell fired from a mortar that exploded in a fireworks-like display over Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor was the shot that began the Civil War. A century and a half later, I decided to experience what it was like to be a Federal soldier in the fort before that event took place.

In the wee morning hours of April 12, 1861, historians agree that the star shell fired from a mortar that exploded in a fireworks-like display over Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor was the shot that began the Civil War. A century and a half later, I decided to experience what it was like to be a Federal soldier in the fort before that event took place.

After weeks of searching the internet to make the contacts for the opportunity to do so, months of acquiring the necessary accoutrements, and many dollars spent in those acquisitions, I was ready to enter the time machine to undertake the living history exercise of the life of a lowly private garrisoned in Fort Sumter seven score and ten years ago. The requirements were strict. The uniform had to conform to the regulations of the pre-Civil War Federal army with obvious differences from the run-of-the-mill reenactor outfit. The headgear was black hat with the left brim turned up (commonly known as the Jeff Davis hat), rather than the forage cap commonly seen in images of Civil war solders. The frock coat was trimmed with red piping of the artillery branch on the frock coat (the unit represented was the 1st U.S. Artillery, Company E) not the blue of the infantry branch, both of which have been carried down to the present day. The more expensive to produce dark blue trousers and leather canteen strap than the cheaper sky blue trousers (cheaper dye) and cloth canteen strap for the hundreds of thousands of Federal troops during the war.

The musket was the heavier .69 caliber smooth bore M1842 Springfield than the later M1861 .58 caliber rifled musket. The manual of arms for the musket was different from the one that most present re-enactors use, much more similar to the one used by the French army during the reign of Napoleon.

After a detour to visit my brother in Tennessee, I drove to Charleston doing a ride share with a Kentuckian on his way to join the 1st South Carolina Infantry. At breakfast in the hotel where we stayed the night before the day that we were to register to participate in the living history events, we were both in our 19th century garb, and grabbed the attention of the others in the hotel’s restaurant. We immediately started a debate about the “right” of a state to secede from the Federal Union, to the onlookers’ delight.

When we arrived at registration at Fort Moultrie (from where the Federal troops departed for Fort Sumter December 26, 1860 because of its indefensible position) he assigned location of my Confederate comrade’s 1st South Carolina Regiment, it became apparent that there was as much uncertainty as to what would happen next as there was a hundred and fifty years ago. The continuing resolution that provided for the funding of the Federal Government was due to expire at midnight that day (April 8th) and would effectively close the National Park Service that managed both Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter (previously unoccupied but far more defensible on an island in the middle of Charleston Harbor). 1861 – would Sumter be resupplied, be reinforced, be evacuated; 2011 – would we be permitted to go to Sumter, if we got there would we have to leave, would the 1st South Carolina be allowed to remain at Fort Moutrie, would there be alternative sites for us to at least display our military prowess? Rumors abounded, and a CNN film crew promised that the discussion we were having about the “what ifs” would most likely be on the evening news.

On Friday evening, the Park service decided that we Federals could not go the Sumter because of the uncertainty over the Federal budget. We would bivouac that night at a fire company pavilion for outdoor picnics. However, the 1st South Carolina could bivouac outside Fort Moultrie but would have to move the next morning if the continuing resolution did not pass before midnight by Congress.

We dropped our gear off at the pavilion and parked our horseless carriages in a specially assigned parking lot. When we returned to the pavilion from our parked vehicles, we stepped into the 19th Century. My identity changed to Private Frank Rivers of “Harrison County.” Vermont, an inexplicable mistake on this E Company private’s enlistment papers as there is no Harrison County; perhaps he was from Harrison Falls in Rutland County. This was not going to be a simple, run-of-the mill reenactment; this was a 24/7 living history experience.

Our memorable company first sergeant, who I guessed to be a former Marine non-com introduced himself and began our instruction to the choreography of close order company drill and the unfamiliar pre Civil War manual of arms with a vengeance. He was Lou Gossett. Jr., as drill sergeant Emil Foley in “An Officer and a Gentleman,” R. Lee Emory as Gunnery Sgt. Hartman in “Full Metal Jacket,” Eileen Brennan as Captain Doreen Lewis in “Private Benjamin” and Warren Oates as Sgt. Hulka in “Stripes” all rolled into one.

After our initial hours of drill, we fell out for supper of lumpy grits and were each issued a hunk of smoked bacon for our haversack. No one asked for seconds. Then more drill until after dark and assignments to three squads each commanded by a corporal. I chose to bed down outside the pavilion to sleep under the stars and discovered that I shared the environment with sand fleas who taught black flies, no-see-ums and mosquitoes everything they know about making life miserable for humans.

The next morning, Saturday, April 9th, we awoke to reveille by our very own drummer boy. We learned that we were indeed going to Fort Sumter as Congress passed the continuing resolution the previous evening (there went my 15 minutes of fame on CNN comparing the uncertainty of 150 years ago and the present). The boat to Sumter was to leave at 7 A.M., not enough time to enjoy a gourmet breakfast of the bacon in our haversacks. We geared up and marched about three blocks to Fort Moultrie, from where we were to leave and our actual counterparts left to sail to Sumter a century and a half ago.

Immediately the timeless military reality of “hurry up and wait” was equally applicable to our unit. We got to the point of departure at seven, but no boat. The first sergeant recognized it was an opportune time to sharpen our “regular army” appearance for the visitors to Sumter. We drilled and drilled and drilled. He introduced us to a new command that may not have been historically accurate, but made necessary by the sand fleas, “Company – Scratch!” This followed the information that the command “Attention!” did not include scratching the sand fleas burrowing into our skin.

Finally, after a couple of hours of drill, our transportation came to the dock and we boarded the craft to take us to Sumter. We got there just as the first tourists were arriving and our commanders determined that they did not come to see us eating breakfast. Therefore, the first squad was to load and fire by the numbers (10 to be exact) and the third squad (mine) became the guard detail. The second squad without a particular assignment had the opportunity to unpack their gear and get ready for the next assignment.

My post was to prevent the tourists from walking in front of the firing squad demonstrating volley firing in two ranks. The rest of the squad staffed other guard posts within the fort, and the entire squad would march to each post where a member of the squad would stand guard for an hour. During that hour, one’s musket could not touch the ground (held at [left] shoulder arms, support arms or right shoulder shift) and each of us remained either stationary or marching back and forth, depending upon the post, until relieved by the next squad going through the same drill. The second squad relieved us, which then put us in line to do the volley firing, and the first squad time to unpack.

Each squad fired volleys “by the numbers” –

1. Load in ten times – LOAD: put the musket in position to begin the process

2. Handle – CARTRIDGE: get a paper cartridge from the cartridge box

3. Tear – CARTRIDGE: tear the end of the paper cartridge open with teeth

4. Charge – CARTRIDGE: pour the gunpowder in the cartridge down the barrel of musket

5. Draw – RAMMER: pull the rammer out from under the barrel

6. Ram – CARTRIDGE: push the powder down into the firing chamber

7. Return – RAMMER: put the rammer back under the barrel

8. Cast – ABOUT: make a half turn right and bring musket to hip

9. PRIME: reach into cap box on belt, pill out percussion cap and place on nipple of musket

10. Shoulder – ARMS: bring musket onto left shoulder in a vertical position. Then:

READY: get in firing position and cock the musket

AIM: bring the musket to right shoulder and aim in toward the foe

FIRE: self-explanatory

We then prepared to fire a second volley without the ten step commands, and when the entire squad is at shoulder arms (number 10) the commands: READY, AIM, FIRE are repeated. Unfortunately, many of our muskets misfired (including mine). Each time there was a misfire, a black powder safety officer had to inspect our musket and Clean out the gunpowder by a device that fit on the nipple of the musket after removing the percussion cap and blew out the gunpowder that did not fire. However, we all faked it and the audience did not notice which musket fired and which did not.

Finally, we had the opportunity to unpack our gear and take a break. Unfortunately, our assigned area was a place in the sun in temperatures that were in the eighties. The wool uniforms and no food were beginning to have their effect on some of us (including me). I pulled out my frying pan, cut some chunks off my slab of bacon in my haversack and went to the cooking fire. That became my daily ration plus some undercooked rice. This was also the only food available to the Sumter garrison 150 years ago because the only supply ship, the Star of the West, attempting to supply Fort Sumter was fired upon when it tried to enter the harbor and left before dropping off any supplies, and the Charleston authorities initially allowed no fresh food to be sent to Sumter.

The concern of our first sergeant for our welfare became apparent when he insisted that we drink one canteen of water every hour. He explained that if our urine were clear we would be OK, if it was yellow, we were in trouble and needed to get help, and if it were brown, we would be dead. He paid particular attention to anyone in distress and made sure that person was all right before returning to duty.

If you look closely, you can see me behind the right shoulder of the soldier standing guard duty. I found a shady spot and got a few minutes of sleep to make up for the lack of sleep the previous night.

The last of the tourists left the fort by 5 P.M. Daylight Savings Time. However, we were on “Sumter time” by order of the Major who recreated the identity of the fort’s commander, Robert Anderson. There were no time zones 150 years ago, and the high point of the sun was noon. That resulted in a 90-minute difference in time between the 21st and 19th centuries. We had the fort all to ourselves except for the few security personnel employed by the Park Service.

As sunset turned the sky a hazy purple, we had to fall in and march to the fort’s flagpole located on a rise above the fort. There, we stood at attention as the designated flag detail lowered the huge garrison flag, an exact reproduction of the 33 star flag that flew over the fort until evacuated on April 14th. Note that the fort’s occupants did not consider that they surrendered. Evacuation was always an option discussed by both the Buchannan and Lincoln Administrations, and made known to the fort’s command. However, when the food and ammunition ran out, Major Anderson followed earlier orders that he received when he took command of the fort in November of 1860 to evacuate the fort when and if occupying it was no longer possible.

Yours truly is on the extreme right of the third squad standing directly behind Major Anderson. Our corporal on the left was the tallest of the non-commissioned officers, and commanded the shortest members in the company.

As tired as we were, this was a very solemn ceremony. It indeed was the high point of the day. Now we thought our day was over. Wrong! Guard duty would continue throughout the night.

However, the threat of rain brought us into the casemates (the area where the big guns were located protected by brick enclosures), to sleep. Several bales of hay were to become the stuffing for our mattress tics to soften the impact of brick floors on our poor, aching bodies (I had special dispensation to use an inflatable camping mattress rather than surrender to hay fever). At least the sand fleas did not bother us.

As I was just falling asleep, our corporal called a squad meeting. Orders from above put us on guard duty was to be from two until 4 A.M. However, those leaving the next day, including our corporal, were concerned about being able to keep your eyes on the road and your hands upon the wheel. There was talk about refusing to do the guard duty. Since we were doing living history, I was concerned that the penalty for not standing guard was death, recalling Vermont’s own Private William Scott, “the Sleeping Sentry,” and that the mornings living history exercise would be to stand in front of the firing squad rather than behind it. Finally, we resolved that since we had double the number in our squad, as there were guard posts, each half of the squad would do one hour of sentry duty instead of each one doing two hours.

Sleep was difficult. The responsibility of relieving the guard at 3 A.M. constantly interrupted my rest. Finally, I could sleep no longer, and I arose looking for the member of my squad I was to relieve. Silhouetted in the dim light and wearing an identical uniform as the original 1st U.S. Artillery, the sentry appeared as a ghost in the dim light that would stand guard over the fort for eternity.

Walking guard mount on the fort’s parade ground in the still of the night was an experience that is almost impossible to describe. Although the upper casemates were gone, destroyed by Federals in their bombardment of the fort to seal off Charleston harbor during the blockade, they reappeared in my mind through the night mist dimly reflecting the fort’s security lights, cloned one by one from the lower casemates that survived the shelling. The chorus of snoring of the remainder of the company provided the same soundtrack for me that a sentry heard marching the same post 150 years ago. The night air gave me the same cooling caress that my predecessor experienced. The spirits of the original Company E whispered to me, telling me they, too, contemplated the solitude of marching guard post under the night sky, while the rest of the command slept. Sunrise would end that solitude and the stress of uncertainty would again fill our minds with the angst of uncertainty of what we would face with the coming day.

However, another, more malevolent, spirit visited me that night. Of the 600,000 deaths in the Civil War, 450,000 were not combat related. One of the most common causes of non-battlefield death was dysentery, a symptom of which was diarrhea. The soldiers called it the “Tennessee Quickstep and step quickly I did. It would have been a laughing matter, but with lack of sleep, the quality of the food, the heat of the South Carolina sun and the physical requirements of a soldier, dehydration could become a real threat to health. Nevertheless, I was determined to remain at the fort as long as possible.

Again, our drummer boy beat out reveille and brought us all out of our restless sleep. We hurried to come to attention for the flag raising ceremony.

The Major is facing the company, our Corporal is on the right and the First Sergeant is on the left of the company formation. The Major is carrying the flag under his left arm, the flag raising detail is about to fall out, the First Sergeant will take the flag from the Major, and deliver it to the flag raising detail that will then attach the flag, and the First Sergeant will run it up the flagpole.

After the flag raising ceremony, the First Sergeant reminded us of the need to hydrate. We fell out for breakfast. My condition was not improving, and nothing on the menu (greasy bacon and undercooked rice) appealed to me. However, we were eating the same delicacies that graced the tin plates of our predecessors a century and a half earlier.

We began getting organized for the invasion of the day’s tourists. Third squad was up first for volley firing. As we were getting ready to load by the numbers, the Park Service black powder safety officer suggested we use a charge and a half to make sure all of our muskets fired this time. My delicate condition and the change in loading procedure adversely affected my military bearing, and the Major pulled me out of the formation for individual training in the manual of arms of the “school of the soldier.”

For an hour and a half, the Major had me repeat the manual of arms until my proficiency improved to the point that my skills could have made me a poster child for the illustrations in the pre-Civil War field manual, School of the Soldier. While my individual training was occurring, a television news crew was filming both the Major and me. I found out that the crew was from Al-Jazeera. Seeing my weapons training as a representative of the United States Army no doubt resulted in Bin Laden dropping his guard leaving him vulnerable to members of our military who were much more proficient with their more sophisticated weapons.

After my training that will serve me in good stead in future reenacting, a sack of supplies came from the commander of the Confederate forces poised to begin firing their artillery at the fort. This was an actual event, and as the original Major Anderson, or commander directed that the supplies be returned as he was unwilling to accept any gratuities from those who were about to begin combat. However, unlike his predecessor, our commander turned a blind eye while the enlisted soldiers helped themselves to Lucifers (matches), candles, peanuts and other delicacies included in the offerings from our foes.

As noon approached, Company H would arrive at the fort relieving Company E. The Park Service limited the number of reenactors in the fort to fifty at any one time; therefore, the command consisted of two companies occupying the fort at separate times allowing more than fifty to participate. The original garrison consisted of both Companies E and H consisting of approximately 80 soldiers, so using the company designations for the two shifts Company E was at the fort until Sunday, April 10th, and would leave when Company H arrived. Several, including myself, had signed on to participate in Company H until Thursday, April 14th, the day that the Federal forces evacuated the fort before the Confederates occupied it for the remainder of the war. As my condition was not improving, I finally decided to leave with the rest of Company E.

As we prepared to leave, we said our goodbyes and promised to look for each other at the next big reenactment, First Bull Run (Northern moniker) or First Manassas (Southern Moniker) in July. Group photographs preserved images of our officers, sergeants and corporals. In spite of all the trials and tribulations, his living history exercise was a once in a lifetime event. I would do this again in a heartbeat.

The First Sergeant is on the extreme left (standing), the two Corporals commanded the first and second squads, and the Major is in the front row wearing a forage cap. None of our squad made it into this picture.

When our boat got to shore, I met the Captain commanding Company H assuming the identity of Truman Seymour, born in Burlington, Vermont, and attended Norwich University until he received his appointment to West Point. A few days later, after a doctor’s appointment, I was well enough to visit the camps of the Confederate artillery reenactors firing blanks at the fort. I was proud to hear from other tourists returning from Fort Sumter praise the more disciplined appearance of our representation of the 1st U.S. Artillery Companies E and H.

As a postscript, on my way home I stopped by Fort Monroe, near Hampton, Virginia, that the Defense Department was going to decommission this fall. I wanted to see it before it was no longer a military installation.

Fort Monroe, much more invulnerable than Fort Sumter, and reinforced after Sumter’s evacuation of Fort Sumter, remained in Federal hands and was a major staging area for expeditions against the Confederate coast throughout the war. One of the regiments sent as reinforcements to Fort Monroe was 1st Vermont Infantry, mustered into Federal service for 90 days under the assumption that the war would be over in that time. The 1st Vermont was the first organized body of troops to step foot on the soil of the Confederacy on May 23, 1861. The newly appointed commander of at Fort Monroe, Major General Benjamin Butler, had ordered the regiment to reconnoiter the town of Hampton for enemy troops.

During the Vermonters foray into enemy territory, several slaves joined them and followed the regiment back into the fort. The question then arose, what to do with these slaves? Lincoln, trying to keep what was left of the Union together, was doing everything possible not to alienate the four slave states that were tottering on seceding: Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland and Delaware. He wrote in a letter at that time, “I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor, as I think, Maryland.” For example, if Maryland joined the Confederacy, Confederate states would surround Washington, D.C., the Federal Capital.

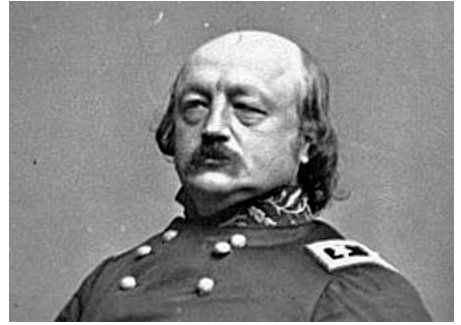

Fortunately, General Butler, Fort Monroe’s commanding officer, and separated at birth from NYPD Blue’s Dennis Franz, was a skilled attorney before he launched his military career. The slaves’ master, a Confederate Colonel, send an emissary to the fort to demand the return of his “property,” by enforcing the appropriate clauses of the Fugitive Slave Law. Butler had prepared carefully framed legal arguments to deny that demand.

Butler challenged the right of the colonel to seek the return of the three individuals under the Fugitive Slave Law enacted by Congress to placate the South before the war. In light of the fact that Virginia now claimed to be no longer part of the United States, that law had no effect in a foreign country. He suggested that the colonel come to Fort Monroe and take the Oath of Allegiance to the United States to obtain the benefits of its laws.

Butler was not content simply to negate the Confederate Colonel’s claim of standing. In addition to the lack of jurisdiction in a “foreign country,” to be governed by the laws of the United States, Butler then presented the Federal government’s own “property” rights superior to those of the colonel. During their initial interview by Butler, the three individuals claimed that the colonel was going to send them further south away from their families to build fortified defenses for the Confederacy along its Atlantic coast.

Courts had long recognized the principle of a belligerent nation’s right to prevent injury done to itself by assistance to the enemy, and it has the right to use the means necessary for its prevention. That includes seizure of property as “contraband of war,” as noted by Chief Justice John Marshall writing for the Court in Church v. Hubbart, 6 U.S. (2 Cranch) 187, 234-35 (1804).

Since slavery was essential to the Southern economy, virtually anything that a slave did contributed to its war effort. The contribution of building coastal fortifications to the Confederacy’s war effort was a no-brainer. Now Lincoln had the perfect answer to the slavery question, as the slaves in the Border States that remained in the Union were not involved in a war effort against the Federal government, and anyone in the Confederacy forfeited their rights to the “contrabands” entering the lines of the Federal troops.

General/Lawyer Butler’s decision to not return the slaves that followed the 1st Vermont into Fort Monroe on May 23, 1861, to their masters changed the Civil War from a fight over the politics of states’ rights into a moral war. It also planted the seed of hope with thousands of human beings escaping the bonds of slavery by entering Union lines with their families in any way they could of one day being free and equal citizens of the United States.